Nick Sabanâs lasting impact on Alabamaâs campus, students: âThat pride showsâ

When Nick Saban signed on as Alabama’s head football coach in 2007, the McFarland Mall was still standing, Mercedes-Benz Amphitheater was just a ballpark, and you couldn’t call an Uber from the Strip.

The University of Alabama itself had almost half as many students and buildings than it does today.

For more than 15 years, the school’s athletic success has accompanied record growth on and off campus. Now, after Saban’s departure, admissions staff are hopeful they can continue to keep enrollment high.

Previously known as The Ferguson Center, the University of Alabama Student Center on campus. University of Alabama students brought their umbrellas and raincoats on a wet first day of the fall semester Wednesday, Aug. 17, 2022. (Ben Flanagan / AL.com)

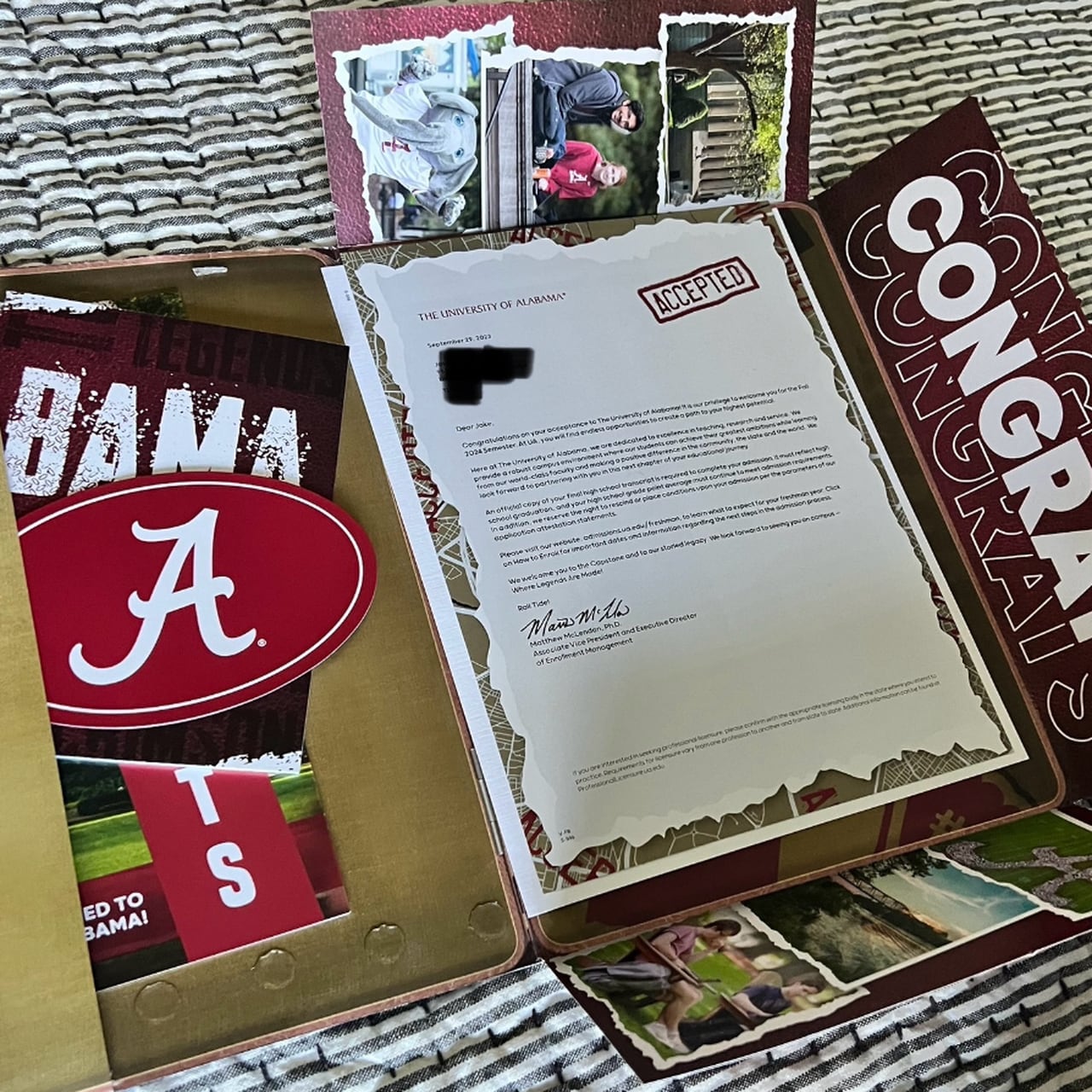

“I wouldn’t necessarily say that we’re going to drastically change the strategy,” Matthew McLendon, the college’s executive director of enrollment management, told AL.com.

“As I joke with people, I’m always happy when we have a national championship,” he said. “But at the same time, there’s a lot of good things about the University of Alabama, that once people get to know us, they start to see.”

Officials were always quick to defend Saban’s multimillion dollar salary, saying the head coach brought in dividends for the campus. As former chancellor Robert Witt put it, Saban was “best financial investment” the university had ever made.

Between 2007 and 2022, enrollment at the University of Alabama has increased by 51%, from 25,580 to 38,645 students.

In that same time, the college more than tripled its endowment, surpassing a record $1 billion in 2022. It also has nearly doubled its physical footprint, adding an engineering quad, the country’s largest Starbucks, and state-of-the-art dorms and recreational facilities, among other massive capital projects.

With two weeks left until move-in, workers are finishing up the final touches on Tutwiler Hall, a $150 million project that was under construction for two years. Rebecca Griesbach / AL.comRebecca Griesbach / AL.com

But just how much does the school’s football program have to do with attracting new students?

It’s a question that McLendon, who has directed enrollment efforts at the University of Alabama since 2019, said he gets a lot.

The school’s athletic success, he said, often draws prospective students in, but it’s not the main factor in their decisions.

According to university data, freshmen applications have almost doubled in the past decade, with out-of-state students making up 79% of applicants last fall. But typically, between 18% and 25% of students who are accepted into the college decide to enroll.

“I’m grateful for the athletics tradition, I am,” McLendon said. “It’s something that everybody’s really proud of, and that pride shows in the recruiters when they go out to the high schools, it shows in the alumni when they talk about the place. So it really does have a lot of good benefits. But there’s a lot of other things about this place that make a student want to want to come here.”

University of Alabama students brave through the sweltering heat and play volleyball during the first day of classes Wednesday, Aug. 23, 2023. (Ben Flanagan / AL.com)

In 2016, just after the team clinched its fourth national title under Saban, The New York Times chronicled the efforts of recruiters as they traveled across the country, working to lure in prospective freshmen from Dallas to Los Angeles to New Jersey.

“Since Nick Saban brought Alabama into an era of football dominance, the school’s application numbers have steadily risen,” the Washington Post wrote in 2018, in another examination of the athletic program’s impact. “But interest in the school was already trending upward.”

Moments after the Crimson Tide clinched a 16th national title, fans near the University of Alabama campus in Tuscaloosa did what they always do after big wins away from home on Jan. 11, 2016. (Ben Flanagan / AL.com)

At the time, the school was the fastest-growing flagship in the country – thanks in part to a ballooning out-of-state student population. At the growth bubble’s peak in 2018, 59% of full-time students were not Alabama residents. That proportion is now about 55%.

CNN anchor Kaitlan Collins, a Prattville native and 2014 UA graduate, was a freshman in high school when Saban got the head coach job and is one of several who have seen first-hand how the campus has changed.

“For him to leave is such a sea change, for me personally as a fan and for so many people,” she told AL.com recently. “I do think it’s bigger than football because people appreciate what he’s done for the school. Every time you go back to Tuscaloosa, there’s some new building on campus or you meet new students who come in from Boston or L.A. And they’re going to Alabama because of the football program and its excellence.”

University of Alabama student Anastasia Taggart brought a Nick Saban prayer candle to his statue outside Bryant-Denny Stadium moments after news broke the Crimson Tide football coach would retire Wednesday, Jan. 10, 2024. (Ben Flanagan / AL.com)Ben Flanagan

The school also began to place more of an emphasis on attracting students with high test scores by investing big on merit scholarships.

In 2022-23, the University of Alabama spent $177 million in merit aid, more than twice what it allocates to students with financial need, according to institutional data. According to The New York Times, the school spent just $8 million on merit aid in 2006.

In turn, the school has seen rapid growth in its once fledgling Honors College, and has enrolled a record number of more than 1,000 National Merit Scholars.

In the next few years, officials plan to keep undergraduate enrollment high while also growing the university’s graduate student population. The college’s current strategic plan also places more emphasis on closing achievement gaps and improving graduation rates.

The University of Alabama enrolled a record class of more than 8,000 freshman in the fall of 2023.AL.com

Recently, McLendon said, admissions staff have made it a specific goal to grow the school’s in-state population. Recruiters aim to visit every high school in the state at least once a year, he said, and this year the college plans to expand its Alabama Advantage Program, which provides tuition assistance for in-state students who are eligible for federal aid.

While out-of-state students still make up a majority of the school’s population, the university has increased the number of freshmen from Alabama for five years in a row.

“We’re doing our best to recruit students from the state of Alabama and try to serve the state of Alabama,” he said. “Now, that said, we are popular as for out-of-state students, I won’t deny that either. There’s a lot of out-of-state students who see the athletic traditions, they see Greek life, they see all of what we offer here and they say yes, I’d like to be a part of that. But when it really comes to the focus of my team and what I’ve been charged with, it really is very clear that we need to make Alabama the priority.”

The next few months, he said, will be a critical time for admissions as students start to weigh their college options. Those choices often come down to what aid is offered, and what access they’ll have to certain programs and opportunities.

“It’s a big change – 16, 17 years of a really successful football coach, you have to expect there to be some change,” he added. “But I think we’re kind of well positioned to adapt to a changing marketplace because we have already. We’re pretty nimble and I’m proud of that.”